The distinction between liquidated damages clauses and penalty clauses

[edit] Introduction

Students of construction law love writing papers about the distinction between liquidated damages clauses and penalty clauses. Traditionally, it has been relatively firm ground, and in particular, everybody trots out the dicta of Lord Dunedin in Dunlop v New Garage.

But things have begun to change. First there was the decision of the High Court of Australia in Andrews v ANZ. Then there was the follow up decision in Paciocco. Now there’s been the decision from England in Cavendish v El Makdessi.

If you have got one of those old papers, which trots out the famous dicta of Lord Dunedin, you might as well throw it away. Quite what we have in its place depends somewhat on where you sit in the common law world. Also changed, but not quite gone, is the interesting but still speculative notion that some time bar provisions, which contain particularly onerous notice provisions, might be circumvented by the equitable doctrine of relief from forfeiture.

Before getting to these new cases, we should acknowledge what is being buried.

[edit] Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v New Garage and Motor Co Ltd

As noted in Cavendish, “Lord Dunedin’s speech in Dunlop achieved the status of a quasi-statutory code in the subsequent case-law”:

- Though the parties to a contract who use the words ‘penalty’ or ‘liquidated damages’ may prima facie be supposed to mean what they say, yet the expression used is not conclusive. The court must find out whether the payment stipulated is in truth a penalty or liquidated damages. This doctrine may be said to be found passim in nearly every case.

- The essence of a penalty is a payment of money stipulated as in terrorem of the offending party; the essence of liquidated damages is a genuine covenanted pre-estimate of damage (Clydebank Engineering …).

- The question about whether a sum stipulated is a penalty or liquidated damages is to be decided upon the terms and inherent circumstances of each particular contract, judged of as at the time of the making of the contract, not as at the time of the breach (Public Works Comr v Hills and Webster v Bosanquet).

- To assist this task of construction various tests have been suggested, which if applicable to the case under consideration may prove helpful, or even conclusive. Such are:

- (a) It will be held to be penalty if the sum stipulated for is extravagant and unconscionable in amount in comparison with the greatest loss that could conceivably be proved to have followed from the breach. (Illustration given by Lord Halsbury in Clydebank case.)

- (b) It will be held to be a penalty if the breach consists only in not paying a sum of money, and the sum stipulated is a sum greater than the sum which ought to have been paid (Kemble v Farren 6 Bing 141). This though one of the most ancient instances is truly a corollary to the last test. …

- (c) There is a presumption (but no more) that it is a penalty when ‘a single lump sum is made payable by way of compensation, on the occurrence of one or more or all of several events, some of which may occasion serious and others but trifling damage’ (Lord Watson in Elphinstone v Monkland Iron and Coal Co 11 App Cas 332).

On the other hand:

- (d) It is no obstacle to the sum stipulated being a genuine pre-estimate of damage, that the consequences of the breach are such as to make precise pre-estimation almost an impossibility. On the contrary, that is just the situation when it is probable that pre-estimated damage was the true bargain between the parties (Clydebank Case, Lord Halsbury at p 11; Webster v Bosanquet, Lord Mersey at p 398)

Dunlop was not a construction case, but these words have been picked over time and time again in construction cases, particularly by contractors who have finished late and who want to demonstrate that the liquidated damages provision in their contract is in fact penal and hence inapplicable. There have been many occasions in which they have succeeded in this, although in recent times, and particularly since the decision in Philips v Attorney General of Hong Kong, the courts of been increasingly cautious about finding these provisions to be penal.

For more information, see Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v New Garage and Motor Co Ltd.

[edit] Andrews v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd

Andrews v ANZ was not a construction case either, but was to do with whether various charges levied by the banks (the ANZ in this case) were penal and hence unenforceable. It was decided by the High Court of Australia, which is the highest court there is in Australia, and whose decisions have in the past carried considerable weight throughout the common law world (as for example, the decision in Pavey & Matthews v Paul, which abolished the doctrine of quasi-contract in favour of the restitutionary basis for quantum meruit). The Andrews decision departed from the conventional understanding of the penalty doctrine in two important respects.

First, the High Court said that the penalty doctrine is not limited to cases arising out of a breach of contract. This is important in construction contracts, not least because of its possible extension to time bar provisions. Some contracts, instead of saying, “You must give notice if you are delayed” (such that failing to give notice is a breach of contract) merely say, “If you do not give notice of delay, then you do not get an extension of time or any associated money”. Getting rid of this concept of breach means that the penalty doctrine becomes rather more difficult to express succinctly, and instead we got this far from elegant formulation:

In general terms, a stipulation prima facie imposes a penalty on a party (“the first party”) if, as a matter of substance, it is collateral (or accessory) to a primary stipulation in favour of a second party and this collateral stipulation, upon the failure of the primary stipulation, imposes upon the first party an additional detriment, the penalty, to the benefit of the second party. In that sense, the collateral or accessory stipulation is described as being in the nature of a security for and in terrorem of the satisfaction of the primary stipulation. If compensation can be made to the second party for the prejudice suffered by failure of the primary stipulation, the collateral stipulation and the penalty are enforced only to the extent of that compensation. The first party is relieved to that degree from liability to satisfy the collateral stipulation.

Secondly, the High Court said that the doctrine had not, as had been assumed, ossified into a rigid common law rule, but remained a matter of equity, and as such can be applied in a rather more flexible way.

No one quite knows what the long-term effects of the decision is going to be, either generally, or in the context of construction cases. It certainly seems to hold the door open a little wider to contractual provisions being challenged as penal. In particular, it has been speculated that it opens the way to challenging time bar provisions as penalties. The idea is that the contractual provision removing a contractor’s right to extension of time or monetary compensation in the event of delay is collateral or accessory to the primary stipulation that the contractor has to give notice. Views have been expressed for and against this idea, but it remains speculative.

[edit] Paciocco v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited

Then, earlier in 2015, we had Paciocco, a decision of the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia, the leading judgment being given by the much respected Chief Justice Robert Allsop. In particular, he identified difficulties arising from the dichotomy of penalty and genuine pre-estimate of loss. He dealt with this by treating the notion of a genuine pre-estimate of loss is simply the reflexive a penalty saying

- 100…It is not necessary, for the sum to be regarded as a genuine pre-estimate of loss, for the parties to have set the figure by reference to likely loss.

Accordingly:

- The penal character of the provision is derived from the extravagance of the relationship between the payment and the possible loss capable of compensation. If there is no such extravagance present, the provision failure of which (by breach or not) admits of compensation is taken to be a genuine pre-estimate of damage, and not penal in character. This is so, even if the parties do not express the clause to be an agreed pre-estimate of damage and even if the parties did not negotiate or set the amount payable by reference to an estimate of damage.

That decision makes it all the harder to demonstrate that any particular contractual provision is a penalty merely by showing it does not reflect any genuine pre-estimate of loss.

[edit] Cavendish

And now we have the decision in Cavendish or, to give it its full title, Cavendish Square Holding BV v Talal El Makdessi, ParkingEye Limited v Beavis [2015] UKSC 67. It is a decision of what is now known as the United Kingdom Supreme Court, which used to be known as the House of Lords. To avoid confusion, in this post it will be called the House of Lords Supreme Court.

The appeal joined two unconnected cases. The first was a commercial case involving the sale of shares in a substantial advertising and marketing communications group in the Middle East. The second was at the other end of the scale, arising out of an £85 charge for a motorist exceeding the permitted 2-hour stay in a car park. The speeches of the seven Law Lords, taken together, run to over 300 paragraphs. They took the opportunity to thoroughly review the doctrine of penalties.

Indeed, they were invited to abolish it altogether, but declined to do so. There were no dissenting judgements (apart from Lord Toulson to a limited degree with regard to the application of consumer regulations) but they do not all take precisely the same line. There are a few things which clearly emerge from the judgements as a whole.

[edit] Forget Lord Dunedin

The new orthodoxy that has emerged from Cavendish is that it is time to reformulate the test. There were several references to other speeches in that case, noting that

- …none of the other three Law Lords expressly agreed with Lord Dunedin’s reasoning, and the four tests do not all feature in any of their speeches

and the penalty doctrine has now been cut loose – in England now as well as Australia – from the concept of “genuine pre-estimate of loss”:

- In our opinion, the law relating to penalties has become the prisoner of artificial categorisation, itself the result of unsatisfactory distinctions: between a penalty and genuine pre-estimate of loss, and between a genuine pre-estimate of loss and a deterrent. These distinctions originate in an over-literal reading of Lord Dunedin’s four tests and a tendency to treat them as almost immutable rules of general application which exhaust the field. In Legione v Hateley (1983) 152 CLR 406, 445, Mason and Deane JJ defined a penalty as follows:

- “A penalty, as its name suggests, is in the nature of a punishment for non-observance of a contractual stipulation; it consists of the imposition of an additional or different liability upon breach of the contractual stipulation …”

- All definition is treacherous as applied to such a protean concept. This one can fairly be said to be too wide in the sense that it appears to be apt to cover many provisions which would not be penalties (for example most, if not all, forfeiture clauses). However, in so far as it refers to “punishment” and “an additional or different liability” as opposed to “in terrorem” and “genuine pre-estimate of loss”, this definition seems to us to get closer to the concept of a penalty than any other definition we have seen. The real question when a contractual provision is challenged as a penalty is whether it is penal, not whether it is a pre-estimate of loss. These are not natural opposites or mutually exclusive categories. A damages clause may be neither or both. The fact that the clause is not a pre-estimate of loss does not therefore, at any rate without more, mean that it is penal. To describe it as a deterrent (or, to use the Latin equivalent, in terrorem) does not add anything. A deterrent provision in a contract is simply one species of provision designed to influence the conduct of the party potentially affected. It is no different in this respect from a contractual inducement. Neither is it inherently penal or contrary to the policy of the law. The question whether it is enforceable should depend on whether the means by which the contracting party’s conduct is to be influenced are “unconscionable” or (which will usually amount to the same thing) “extravagant” by reference to some norm.

[edit] Relief from forfeiture

For many construction lawyers, the concept of relief from forfeiture is a land law thing, learned at law school but largely forgotten since then. Our eye has been taken off the ball that the doctrine might have anything much to do with penalties. But consider a tenant who is late paying the rent. Or perhaps is in breach – perhaps a minor breach – of some covenant in the lease.

The lease (probably drafted by the landlord’s lawyers to be as aggressive as legal ingenuity can devise) gives the landlord the right to forfeit the lease in these circumstances. We know that equity used to offer relief to the tenant in appropriate cases. As it did to mortgagors. And that statute subsequently codified that relief. And that is because forfeiture would be an extravagant and disproportionate remedy. The concept is not a million miles from that of penalties.

And this is what the House of Lords Supreme Court has now drawn vivid attention to. The first speech of Lords Neuberger and Sumption (Lord Carnwath agreeing) set the scene:

- The relationship between penalty clauses and forfeiture clauses is not entirely easy. Given that they had the same origin in equity, but that the law on penalties was then developed through common law while the law on forfeitures was not, this is unsurprising.

The House of Lords Supreme Court picked up and ran with a concept rolled out in BICC plc v Burndy Corpn [1985] Ch 232, namely that the court’s approach is first to look at the penalty issue, and then, if not satisfied that the clause is penal, to then consider whether to grant relief from forfeiture. Lord Hodge said:

- There is no reason in principle why a contractual provision, which involves forfeiture of sums otherwise due, should not be subjected to the rule against penalties, if the forfeiture is wholly disproportionate either to the loss suffered by the innocent party or to another justifiable commercial interest which that party has sought to protect by the clause. If the forfeiture is not so exorbitant and therefore is enforceable under the rule against penalties, the court can then consider whether under English law it should grant equitable relief from forfeiture, looking at the position of the parties after the breach and the circumstances in which the contract was broken. This was the approach which Dillon LJ adopted in BICC plc v Burndy Corpn [1985] Ch 232 and in which Ackner LJ concurred. The court risks no confusion if it asks first whether, as a matter of construction, the clause is a penalty and, if it answers that question in the negative, considers whether relief in equity should be granted having regard to the position of the parties after the breach.

There are a number of interesting things about this.

First, we have not hitherto been going down this track in construction law. The idea of the twofold test is new.

Secondly, the second ground may be, at least in some cases, wider than the first. The passage is predicated on the possibility that a clause might clear the penalty hurdle, but fall at the relief from forfeiture hurdle.

Thirdly, this second hurdle involves a wider enquiry. The traditional view is that the penalty issue is judged as at the time of the contract, not the time of the breach, and this bit of Dunlop appears to survive. But the relief from forfeiture issue requires the court to look at what has actually happened (if anything) as a result of the breach. Think about the case of a bridge crossing a river as part of a new road through some virgin forest. The bridge contractor is late.

The liquidated damages clause in the bridge contract may well not be penal; at the time of the making of the bridge contract, it might have been perfectly reasonable. But suppose the road either side of the bridge, being constructed by another contractor, is even later? The owner suffers no loss at all as a result of the bridge being late; until the road is built, the bridge is useless. Should the bridge contractor still forfeit the liquidated damages in these circumstances? Or should the courts give relief against that forfeiture? We do not know how this will pan out.

Fourthly, look at the passage again in the context of a notice provision, whereby a contractor forfeits their right to extensions of time, or loss and expense, or payment for variations, unless they give notice in a specified form by a specified time. That looks, at first blush, well within the doctrine. And even though the court might decide that such a time bar is not penal, it might nevertheless conclude that the failure to give notice was in the event of no practical consequence whatsoever, since the owner knew perfectly well of the relevant event, of its likely impact on time and cost, and that the contractor would be making a claim for it. And so all of the legitimate purposes of the notice provision are otherwise satisfied. Should the court grant relief from forfeiture in these circumstances? It looks arguable, but again we will have to wait and see what courts do with the argument.

So, how had we all missed this? Partly, it is because it was widely assumed for a long time that the equitable doctrine of relief from forfeiture had been entirely subsumed by the statutory codification of the doctrine in the case of forfeiture of mortgages and leases. But in Shiloh Spinners Ltd v Harding [1973] AC 691 the House of Lords had said, “Oh no. The old equitable doctrine still applies in other contexts”. That case was highlighted recently by the Privy Council in Cukurova Finance International Ltd & Anor v Alfa Telecom Turkey Ltd (British Virgin Islands) [2013] UKPC 2.

This is how Lord Wilberforce had put it in Shiloh:

- There cannot be any doubt that from the earliest times courts of equity have asserted the right to relieve against the forfeiture of property. The jurisdiction has not been confined to any particular type of case…I would fully endorse this: it remains true today that equity expects men to carry out their bargains and will not let them buy their way out by uncovenanted payment. But it is consistent with these principles that we should reaffirm the right of courts of equity in appropriate and limited cases to relieve from forfeiture for breach of covenant or condition where the primary object of the bargain is to secure a stated result which can effectively be attained when the matter comes before the court, and where the forfeiture provision is added by way of security for the production of that result. The word ‘appropriate’ involves consideration of the conduct of the applicant for relief, in particular whether his default was wilful, of the gravity of the breaches, and of the disparity between the value of the property of which forfeiture is claimed as compared with the damage caused by the breach.

Note the reference to “limited cases”. Viscount Dilhorne also emphasised this:

- that the cases in which it is right to give relief against forfeiture where there has been a wilful breach of covenant are likely to be few in number and where the conduct of the person seeking to secure the forfeiture has been wholly unreasonable and of a rapacious and unconscionable character.

Again, it might be thought that this formulation might include cases where a contractor’s right to time or money is forfeit by a failure to give a prescribed notice, and where the primary objects of a notice provision are effectively otherwise attained. But what about the reference to conduct “of a rapacious and unconscionable character”?

In many cases, of course, reliance by an owner on a liquidated damages clause or time-barring notice provision is reasonable, but there are other cases – where they have suffered no loss at all and, in the case of a notice provision, the evident purpose of the drafting of the clause was to prescribe the practically impossible, laying a trap so to speak – where it might well be said that there is rapaciousness and unconscionability.

[edit] Scaptrade

But what about Scaptrade? That decision (more fully Scandinavian Trading Tanker Co AB v Flota Petrolera Ecuatoriana; The Scaptrade) was a case in which an attempt was made to extent Shiloh to a shipping case about a time charter. Lord Diplock said:

- My Lords, Shiloh Spinners Ltd v Harding was a case about a right of re-entry on leasehold property for breach of a covenant, not to pay money but to do things on land. It was in a passage that was tracing the history of the exercise by the Court of Chancery of its jurisdiction to relieve against forfeiture of property that Lord Wilberforce said ([1973] 1 All ER 90 at 100, [1973] AC 691 at 722):

- ‘There has not been much difficulty as regards two heads of jurisdiction. First, where it is possible to state that the object of the transaction and of the insertion of the right to forfeit is essentially to secure the payment of money, equity has been willing to relieve on terms that the payment is made with interest, if appropriate, and also costs.’

- That this mainly historical statement was never meant to apply generally to contracts not involving any transfer of proprietary or possessory rights, but providing for a right to determine the contract in default of punctual payment of a sum of money payable under it, is clear enough from Lord Wilberforce’s speech in The Laconia. Speaking of a time charter he said: ‘It must be obvious that this is a very different type of creature from a lease of land.’

- Moreover, in the case of a time charter it is not possible to state that the object of the insertion of a withdrawal clause, let alone the transaction itself, is essentially to secure the payment of money. Hire is payable in advance in order to provide a fund from which the shipowner can meet those expenses of rendering the promised services to the charterer that he has undertaken to bear himself under the charterparty, in particular the wages and victualling of master and crew, the insurance of the vessel and her maintenance in such a state as will enable her to continue to comply with the warranty of performance.

- This, the commercial purpose of obtaining payment of hire in advance, also makes inapplicable another analogy sought to be drawn between a withdrawal clause and a penalty clause of the kind against which courts of law, as well as courts of equity, before the Judicature Acts had exercised jurisdiction to grant relief. The classic form of penalty clause is one which provides that on breach of a primary obligation under the contract, a secondary obligation shall arise on the party in breach to pay to the other party a sum of money which does not represent a genuine pre-estimate of any loss likely to be sustained by him as the result of the breach of primary obligation but is substantially in excess of that sum. The classic form of relief against such a penalty clause has been to refuse to give effect to it, but to award the common law measure of damages for the breach of primary obligation instead. Lloyd J in The Afovos attached importance to the majority judgments in Stockloser v Johnson [1954] 1 All ER 630, [1954] 1 QB 476, which expressed the opinion that money already paid by one party to the other under a continuing contract prior to an event which under the terms of the contract entitled that other party to elect to rescind it and to retain the money already paid might be treated as money paid under a penalty clause and recovered to the extent that it exceeded to an unconscionable extent the value of any consideration that had been given for it. Assuming this to be so, however, it is incapable of having any application to time charters and withdrawal notices. Moneys paid by the charterer prior to the withdrawal notice that puts an end to the contract for services represent the agreed rate of hire for services already rendered, and not a penny more.

- All the analogies that ingenuity has suggested may be discovered between a withdrawal clause in a time charter and other classes of contractual provisions in which courts have relieved parties from the rigour of contractual terms into which they have entered can in my view be shown on juristic analysis to be false. Prima facie parties to a commercial contract bargaining on equal terms can make ‘time to be of the essence’ of the performance of any primary obligation under the contract that they please, whether the obligation be to pay a sum of money or to do something else. When time is made of the essence of a primary obligation, failure to perform it punctually is a breach of a condition of the contract which entitles the party not in breach to elect to treat the breach as putting an end to all primary obligations under the contract that have not already been performed. In the Tankexpress case this House held that time was of the essence of the very clause with which your Lordships are now concerned where it appeared in what was the then current predecessor of the Shelltime 3 charter. As is well known, there are available on the market a number of so-(mis)called ‘anti-technicality clauses’, such as that considered in The Afovos, which require the shipowner to give a specified period of notice to the charterer in order to make time of the essence of payment of advance hire; but at the expiry of such notice, provided it is validly given, time does become of the essence of the payment.

- My Lords, quite apart from the juristic difficulties in the way of recognising a jurisdiction in the court to grant relief against the operation of a withdrawal clause in a time charter, there are practical reasons of legal policy for declining to create any such new jurisdiction out of sympathy for charterers.

Scaptrade was relied on in the first instance decision in The Padre, which was mentioned in another context in Cavendish, but apart from that indirect reference, Cavendish does not refer to Scaptrade at all. Which is a bit of a puzzle. Because the discussion of the relief from forfeiture doctrine in Cavendish suggests precisely what Scaptrade says you cannot do, namely apply the doctrine in commercial cases which concern only payment of money, not proprietary interests. The assumption has been that Scaptrade prevents any incursions of the relief from forfeiture doctrine into construction cases, but it is probably time now to review that assumption.

[edit] Cavendish treatment of the Australian cases

What did the speeches in Cavendish have to say about the recent Australian cases?

Lords Neuberger and Sumption were not prepared to follow the Andrews line that the penalties doctrine is now free from its link to breach of contract. But Lord Hodge hung on to the notion of disguised penalties:

- The rule may also be criticised because it can be circumvented by careful drafting. Indeed one of Cavendish’s arguments was that clause 5.1 could have been removed from the scope of the rule if it had been worded so as to make the payment of the instalments conditional upon performance of the clause 11 obligations. This is a consequence of the rule applying only in the context of breach of contract. But where it is clear that the parties have so circumvented the rule and that the substance of the contractual arrangement is the imposition of punishment for breach of contract, the concept of a disguised penalty may enable a court to intervene: see Interfoto Picture Library Ltd v Stiletto Visual Programmes Ltd [1989] QB 433, Bingham LJ at pp 445-446 and, more directly, the American Law Institute’s “Restatement of the Law, Second, Contracts” section 356 on liquidated damages and penalties, in which the commentary suggests that the court’s focus on the substance of the contractual term would enable it in an appropriate case to identify disguised penalties.

So, consider these scenarios:

- The contract requires the contractor to complete the building of a house by 30th June, and provides for liquidated damages of $1 million a day if the contractor is late.

- The contract contains no completion date, but provides that the contractor must pay rent of $1million a day if he does not complete by 30th.

The first is plainly penal. In the second, there is no breach of contract if the contractor finishes in July, but the effect of the contract is the same as the first. It is a disguised penalty, so that the penalty doctrine may well be enlivened.

There may be grey areas, such as in the case of lane rental contracts, but the difference between the English approach and the Australian approach might not be so very great in practice.

The approach of Paciocco on the other hand – that all the attention should be on the penalty test and not on the pre-estimate of loss test – was wholeheartedly endorsed, Lords Neuberger and Sumption saying:

- The real question when a contractual provision is challenged as a penalty is whether it is penal, not whether it is a pre-estimate of loss. These are not natural opposites or mutually exclusive categories. A damages clause may be neither or both. The fact that the clause is not a pre-estimate of loss does not therefore, at any rate without more, mean that it is penal.

[edit] Where is this headed?

So, where is all this going? Are the courts shutting down challenges, applying black letter law? Or widening the grounds of challenge? It is some of each, it seems.

Lords Neuberger and Sumption said:

And the speeches were particularly reticent about interfering with commercial bargains on a level commercial playing field negotiated with the assistance of lawyers. But there perhaps a dose of salt should be taken with this, and in the previous breath, they said

- There is a fundamental difference between a jurisdiction to review the fairness of a contractual obligation and a jurisdiction to regulate the remedy for its breach.

They spoke about “the true test” in terms not so very different from Andrews:

- The true test is whether the impugned provision is a secondary obligation which imposes a detriment on the contract-breaker out of all proportion to any legitimate interest of the innocent party in the enforcement of the primary obligation. The innocent party can have no proper interest in simply punishing the defaulter. His interest is in performance or in some appropriate alternative to performance

Or, as Lord Mance put it:

- What is necessary in each case is to consider, first, whether any (and if so what) legitimate business interest is served and protected by the clause, and, second, whether, assuming such an interest to exist, the provision made for the interest is nevertheless in the circumstances extravagant, exorbitant or unconscionable.

For many in the commercial field the concepts of fairness and legitimate business interest might be hard to separate. Usually, where it is possible to say of a provision in a commercial construction contract: “That provision is unfair!”, it will be equally possible to say: “That provision serves no legitimate business interest!”

In the case of liquidated damages clauses, the net effect of Cavendish is probably going to be to make challenges easier. Certainly, a clause is not going to be declared penal unless it is way beyond the pale of what is commercially appropriate, but that was pretty much the situation anyway following cases like Philips v Attorney General of Hong Kong.

But the second wave of attack – in the form of relief from forfeiture – might well succeed in those cases, by no means uncommon, where the liquidated damages are way in excess of the loss, if any, actually suffered by the owner by reason of the late completion.

What about time-barring notice provisions? The application of the Andrews case to these notices remains speculative in Australia. This new attention to relief from forfeiture will add to comparable speculation elsewhere in the common law world. It raises a number of interesting and difficult questions. For example, is it within the jurisdiction of an adjudicator to afford relief against the forfeiture of contractual rights for failure to give notice? To what extent will the courts put unbending enforcement of notice provisions in onerous “hard money” contracts into the “rapacious and unconscionable” basket? Only time will tell.

The original version of this article can be seen at: Penalties – a Brief Guide to Three Recent Revolutions, 13/11/2015 by Robert Fenwick Elliott.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Compensation event.

- Completion date.

- Concurrent delay.

- Damages in construction contracts.

- Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v New Garage and Motor Co Ltd.

- Extension of time.

- Liquidated damages.

- Liquidated v unliquidated damages.

- Loss and expense.

- Measure of damages.

- Oakapple Homes (Glossop) Ltd v DTR (2009) Ltd and others.

- Penalty.

- Privy Council in NH International (Caribbean) Limited v National Insurance Property Development Company Limited (Trinidad and Tobago).

- Relevant event.

- Unliquidated damages.

Featured articles and news

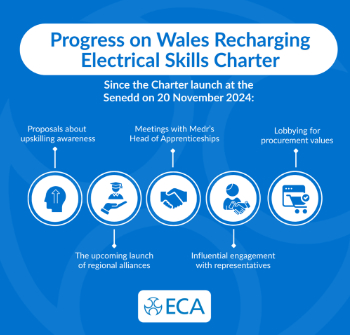

ECA progress on Welsh Recharging Electrical Skills Charter

Working hard to make progress on the ‘asks’ of the Recharging Electrical Skills Charter at the Senedd in Wales.

A brief history from 1890s to 2020s.

CIOB and CORBON combine forces

To elevate professional standards in Nigeria’s construction industry.

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.

Preserving, waterproofing and decorating buildings.

Many resources for visitors aswell as new features for members.

Using technology to empower communities

The Community data platform; capturing the DNA of a place and fostering participation, for better design.

Heat pump and wind turbine sound calculations for PDRs

MCS publish updated sound calculation standards for permitted development installations.

Homes England creates largest housing-led site in the North

Successful, 34 hectare land acquisition with the residential allocation now completed.

Scottish apprenticeship training proposals

General support although better accountability and transparency is sought.

The history of building regulations

A story of belated action in response to crisis.

Moisture, fire safety and emerging trends in living walls

How wet is your wall?

Current policy explained and newly published consultation by the UK and Welsh Governments.

British architecture 1919–39. Book review.

Conservation of listed prefabs in Moseley.

Energy industry calls for urgent reform.